James Hull Articles: Archive X

James Hull is an animator by trade, avid storyteller by night. He also taught classes on Story at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). You can find more articles like this on his site dedicated to all things story at...

James Hull is an animator by trade, avid storyteller by night. He also taught classes on Story at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). You can find more articles like this on his site dedicated to all things story at...NarrativeFirst.com

For additional past articles for Screenplay.com by James Hull, click here.

The Same Story: Aliens and Blade Runner: 2049

Many recognize the similarities in the structure of different narratives. While many point to a familiar sequence of beats seemingly inherited from one generation to the next, the reality is the similarity lies in a like-minded purpose. With shared intent comes a shared structural foundation.

What do Jamie Foxx and Marlin have in common?

Both Collateral and Finding Nemo tell the same exact story.

The Belly of Nonsense

When speaking of similar story structures, we refer to the underlying storyform of the respective narratives, not some heroic journey steeped in the cultural mythos. Refusing the call to grab the sword from the belly of the beast to return with the transformative elixir is not story structure.

It’s seeing the Virgin Mary in a potato chip.

Many believe The Matrix and Star Wars to be the same story; Luke Skywalker and Neo are interchangeable.

They’re not.

Luke doesn’t possess a problem with faith, and Neo doesn’t maintain an issue with trust. While sounding reasonably similar, Faith and Trust inject different motivations into a narrative. Dramatica defines Faith as accepting something as certain without proof, Trust as an acceptance of knowledge as proven without first trusting its validity. One looks to certainty without proof, the other to experience without checking validity. Splitting narrative hairs to be sure, but when trimming a story of the useless and contradictory fat and fluff competency demands accuracy.

The Difference Between Neo and Luke Skywalker is the storyform.

The Storyform and Purpose

The storyform of a narrative is a specific collection of seventy-five story points that function as a carrier wave, transmitting Author’s Intent to an Audience. The story points relate holistically, the nature and meaning of implied story points every bit as important as though specific points set forth by the Author.

Occasionally, completely different stories share the same storyform. Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story exist as one example of shared intent. Aside from the six-week time limit introduced in the more modern telling of dueling families, the core thematic structure rings familiar.

Same with Collateral and Finding Nemo. Marlin and Jamie Foxx’s character Max struggle with the same problem of Avoidance: Marlin is driven to prevent his son from suffering the same fate as his brother and sisters; Max is motivated to avoid following any of his dreams.

Regardless of genre or medium, if individual Authors seek to argue a similar approach to the same exact inequity, the structure of those arguments line up from beginning to end.

The Dramatica theory of story is the first paradigm, or understanding, of story structure that codifies and defines this storyform. Every complete story is an analogy to a single human mind trying to resolve an inequity. The storyform argues an individual approach towards resolving a single inequity. Sometimes it presents this argument through tragedy (Se7en or Hamlet), other times the storyform uses triumph to make its point (Moonlight or Kingsman: The Secret Service).

Both Aliens and Blade Runner: 2049 employ the second means.

Overall Story Throughline

In Aliens the desire to exist and to thrive motivates conflict in every scene. Blade Runner: 2049 shares the same exact motivating force. That inherent survival instinct—whether inherited or programmed—serves as the basis for conflict in both films. The aliens protect their Queen, the replicants rise to fulfill their original programming and claim their rights as something other than slaves. Aliens vs. Space Marines, Humans vs. Replicants—groups on both sides conflict over Desire.

- OS Throughline: Physics

- OS Concern: Understanding

- OS Issue: Instinct

- OS Problem: Desire

- OS Solution: Ability

In a narrative where the Main Character adopts the competing paradigm presented by the Influence Character, the Problem elements of both the Overall Story Throughline and the Main Character Throughline rest on the same element.

Both Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and K (Ryan Gosling) change their Resolve to address the story’s central inequity.

Main Character Throughline

Ripley awakens to find she outlives her daughter. Frozen in the darkness of space for decades, the mother returns home to find her loved one buried and passed on. Absent from the Original Version, the Director’s Cut of Aliens presents critical insights into this personal throughline and explains the pain she feels for a wish that can never find fulfillment and love that cannot find a recipient.

- MC Throughline: Universe

- MC Concern: Past

- MC Issue: Interdiction

- MC Problem: Desire

- MC Solution: Ability

In Blade Runner: 2049 K shares a similar motivation with his overwhelming desire to be loved. Ripley’s willingness to give motherly love harmonizes with K’s hope for that maternal bond.

Many look to the “wants and needs” of a character to express the driving force of a narrative. Here, both narratives explicitly focus on the problems of wanting or lacking. Neo struggles with a Problem of Disbelief; Luke with a Problem of Testing. These elements motivate their “wants and needs,” but they don’t explicitly tell of a problem with wanting something.

K and Ripley do.

A functioning narrative presents an opportunity to see what an inequity looks like both from within, and without the problem. We can’t simultaneously be in our heads and outside of ourselves—stories give us that experience.

Resolving Both Overall and Main Stories

The solution to a problem of Desire is Ability.

Many understand how Faith resolves Disbelief and how Trust concludes Testing. Comprehending how Ability resolves Desire requires a further exploration.

Ripley longs to be a mother to her lost child. It’s once she gains the ability to fight for herself that she sheds this debilitating drive. “Get away from her, you Bitch!” rids her psyche of desire: I can’t do anything about what happened in the past, but I can do something. And what she does is engage in Ability.

This shift also brings a successful conclusion to the Overall Story Throughline. Her change of Resolve grants her the Ability to eject the Queen out of the ship, allowing her, Newt, and Bishop the ability to return home with a greater understanding of what happened on the colony outpost.

The same resolving dynamic manifests in Blade Runner: 2049.

Joi points to K and calls him “Joe,” resulting in a paradigm shift that begins his turn away from Desire. I can’t keep wanting and longing, but there is something I can do.

“Dying for the right cause, it’s the most human thing we can do.”

K sacrifices his wants and desires for the evolution of the collective. He chases Deckard down, chokes out Wallace’s replicant, and safely returns father to daughter—granting them the ability to meet face-to-face finally.[1]

Different galaxies. Different constellations of characters. At the heart, both the Overall Story Throughlines and Main Character Throughlines of Aliens and Blade Runner: 2049 resonate with a similar exploration of thematic structure.

Their particular Influence Character and Relationship Story Throughlines challenge one to look deeper into the storyform.

Influence Character Throughline

With an Overall Story Throughline and Main Character Throughline focused on external Problems of Desire, the nature of the implied story points demand further introspection:

- IC Throughline: Mind

- IC Concern: Memory

- IC Issue: Suspicion

- IC Problem: Perception

If Elvis’ rendition of Suspicious Minds in Blade Runner: 2049 wasn’t enough to inform you of the competing and alternate approach to resolving the inequity, the belief systems of Joi and Deckard should. Both Influence Characters challenge K with their focus on what they know to be true. Their perceptions reign supreme and their drive to alter perception—particularly on the part of Joi—force K to reconsider his point-of-view.

In Aliens, Newt’s illustration of a Problem of Perception steers down a different path. Emanating from the point-of-view of a scared and frightened child, abandoned by her parents at a young age, Newt knows they’re all going to die. The young girl finds herself so locked in her perception of reality, so challenged by the memories of her long lost loved ones, that she doesn’t suspect for one moment that someone can be there for her.

This perspective challenges and influences Ripley the same way Joi challenges K to give in to his ability. Whether looking at a positive application of Perception in Blade Runner: 2049 or a negative instance of Perception in Aliens, Influence Characters in both narratives obstruct their respective Main Characters from remaining in comfort by looking to an element of Perception. Completely different illustrations rising from the same touch point; both necessary to balance out the Problems in the Main Character and Overall Story Throughlines.

Relationship Story Throughline

Blade Runner: 2049 illustrates the Relationship Story Throughline needed to round out the narrative more fully than Aliens. As K and Joi attempt to integrate into each other’s lives, tension mounts as each adapts and changes themselves to fit within the other.

- RS Throughline: Psychology

- RS Concern: Conceptualizing

- RS Issue: State of Being

- RS Problem: Change

Aliens tells of a similar dynamic between mother and daughter but to a lesser extent. The Relationship in Blade Runner: 2049 turns to prostitution and technology to minimize friction between the two, while Aliens turns to conversations regarding dreams and nightmares. Adapting to this new mother/daughter dynamic defines the conflict between Ripley and Newt and resolves with an exclamation of Mommy! as Newt leaps into her arms.

An Approach That Works

A look at the Four Throughlines for Aliens and the Four Throughlines for Blade Runner: 2049 tells of stories with a similar personality.

Their shared storyforms broadcast the same conclusion: A move towards ability resolves an apparent inequity of desire, bringing success and fulfillment. With Aliens, this plays out objectively with Ripley’s stand aboard the mothership and their eventual ability to bring home an understanding of what happened with that lost colony. Subjectively, Ripley resolves the angst for her missed opportunity with a chance to dream of a new one.

Blade Runner: 2049 argues the same approach. Do what you can do, be the person others need you to be, and find success and fulfillment of those desires that held you back. Logistically, K makes it possible for Deckard to reunite with his daughter and for a greater understanding of her birth and the revolution to come. Emotionally, K rests comfortably knowing he is more human than human.

The storyform encodes the message behind the narrative. You can change the setting, change the cast, the period, even specific illustrations of every story point—but you can’t run away from the single approach argued by a particular storyform. Stories exist as models of the way we think and solve problems.

In some respects, a great story is more human than human.

-

Though that glass partition seems to tell of an inability to touch—a greater Understanding of their deep divide. Either way, it satisfies the Overall Story Solution of Ability. ↩

Interested in learning more about stories with similar structures in a fun and visual way. Register now for the Narrative First Atomizer and get to know story at a molecular level. The Narrative First Atomizer breaks down successful narratives into their essential ingredients—providing you the know-how to craft and develop your own meaningful stories. Visit Narrative First to learn more about this exciting service.

The Power of Implied Story Points to Frame a Narrative

Anyone can tell a story. This event happens, then that happens, and then finally that happens. Listing events in chronological order is indeed one way to tell a story—an even better idea is to find a meaningful relationship between those events.

The Dramatica® storyform lists seventy-five individual story points that holistically work together to argue a single approach for solving a problem. One finds over 300 individual storyforms on the central Dramatica site and well over 200 here on Narrative First. Vetted and confirmed by a group of Dramatica Story Experts, these storyforms represent the most accurate way of defining their individual narrative structures.

At least, this was the standard understanding until I taught Story Development at the California Institute of the Arts. In my second year, a group of students successfully challenged the storyform for M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense.

Analysis Part Two

In our first analysis of the film—completed in 1999 as a part of the Dramatica Users Group series-we saw Universe as the context for Malcolm’s problems and Mind the source of impact emanating from Cole’s perspective. Malcolm is dead but doesn’t know it, and Cole’s disturbed nature challenges Malcolm to wake up.

The second analysis—first brought to light by my students more than ten years later—challenged this initial understanding by flopping the Main Character and Influence Character Throughline perspectives. Instead of seeing Malcolm’s problems as a matter of externalized consequences (he’s dead), the students interpreted his issues within the context of a fixed internal mindset (Malcolm doesn’t know he expired). They saw Cole’s influence as coming from a place of Universe and an external state he cannot escape (I see dead people).

Sensing the greater clarity in this new storyform, I presented it to Chris Huntley, co-creator of the Dramatica theory of story, and he agreed that it was a better representation of the film’s narrative dynamics. The correct analysis of The Sixth Sense on the central Dramatica site reflects this better understanding.

The Litmus Test for Domains confirms our decision. If Malcolm suddenly escaped limbo, would that resolve his issues? The answer is no. If Malcolm fled the mindset that he is still alive, would that address his concerns? The answer is yes.

This answer places Malcolm’s Main Character Throughline firmly in Mind.

What is Meant by Implied Story Points

As evidenced by the disparity in Sixth Sense storyforms over time, one can always make an argument for a single story point to the exclusion of others. One could argue Physics or Psychology as the Domain of Malcolm’s personal issues just as quickly and convincingly as the arguments made above for Mind and Universe. It’s when you look to the implied story points that all the other choices begin to pale in comparison.

Malcolm’s perspective in Mind implies Cole’s influence emanates from Universe. Main Character and Influence Character perspectives always sit diagonally across from each other; this ensures the highest amount of conflict and a shared similarity between the kinds of issues they face.

The argument for Malcolm in Mind and Cole in Universe holds up against scrutiny: Cole can’t help but be in the presence of dead people, he can’t escape the situation (Universe). And this problematic perspective eventually draws Malcolm’s to his Changed Resolve.

If the area of conflict from Malcolm’s perspective is in Universe, that implies Cole’s influence emanates from Mind. This arrangement fails to hold up: Cole’s mindset and the mindset around him does not directly challenge Malcolm to move to a Changed Resolve.

We can make a convincing argument for Malcolm in Mind and Malcolm in Universe; the relevancy of one over the other reveals itself when we look at the implied story points based on our choice of Domain.

The Source of Conflict

When it comes to crafting a narrative with the Dramatica theory of story, one must always look to the source of conflict in each Throughline. Cole is sad and lonely because he sees dead people—he doesn’t see dead people because he is sad and lonely.

- I’m sad and lonely because I see dead people (Influence Character in Universe)

- I see dead people because I’m worried and lonely (Influence Character in Mind)

One ascertains this source of conflict while knowing the entirety of the narrative, from beginning to end. The Dramatica storyform captures time and space into a single meaningful document. The story points and appreciations found in the storyform don’t represent a what if?, they tell of What Is.

The revelation that Cole sees dead people arrives halfway through the story yet exists throughout the entire narrative. The reveal reframes everything before in greater context and motivates Malcolm to grow out of his justifications.

Finding the Most Accurate Storyform

Storyforms exist at varying levels of accuracy for a particular narrative—but only one rings true.

Consider the choice of conflict within Malcolm’s Throughline and the implied source of conflict in the alternate Influence Character Throughline:

- I think I’m alive because I’m in limbo (Main Character in Universe)

- I see dead people because I’m sad and lonely (Influence Character in Mind)

This arrangement suggests that Cole’s attitude of being sad and lonely influences Malcolm to escape limbo.

Contrast that storyform with this one:

- I’m in limbo because I think I’m alive (Main Character in Mind)

- I’m sad and lonely because I see dead people (Influence Character in Universe)

This arrangement suggests that Cole’s reality of being stuck around dead people influences Malcolm to realize the lies he tells himself about being alive.

The latter sounds more like The Sixth Sense.

Also, the second alignment of Throughlines offers a reason for Cole and Malcolm to be within the same narrative. They’re both stuck—one internally, one externally—yet the way they proceed couldn’t be more different. Cole’s Chaotic life challenges and impacts Malcolm’s Perception of reality.

Considering the Implications of Choices

We see the world from a subjective point-of-view. This reality blinds us to the real state of things—and creates the need for narratives to understand better the means by which we solve problems.

With the Dramatica theory of story, that subjective blindness falls away. Offering a comprehensive look at all perspectives within a single context, Dramatica fills those blind spots—or story holes—with implied story points. Choosing to see a conflict in one area naturally develops conflict in another.

The key to everything in Dramatica is this: One story point does not identify a story—it’s the nature of the implied story points that determine the accuracy of the structure. The relationship between the perspectives and the story points within frame those implications and create the storyform.

It’s on us to appreciate the totality of the message.

This article originally appeared on Narrative Firsta site dedicated to helping writers flourish and finish their very best work. Want to develop your story sense or learn how to fix your current story? Would you enjoy more articles like the one above delivered to your inbox every week? Join the thousands of novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who subscribe to The Narrative First Weekly Newsletter become a master of your art and craft.

Identifying the Protagonist and Antagonist of a Complete Story

To many, the determination of key players within a narrative remains simple: identify the good guy and identify the bad guy. Unfortunately, assumed notions of morality fail to take into consideration the actual inequity of the story. Sometimes the efforts to resolve an inequity turn out to be a good thing; other times, they do not.

The key towards maintaining the integrity of a narrative from beginning to end lies in the correct identification of the fundamental inequity of a story.

Seeking Resolution of the Inequity

In the article Identifying the Goal and Consequence of a Complete Story, the moment where a story begins determines the type of Goal to resolve it:

to accurately define the objective Goal of a narrative, one must first identify the beginning of conflict–the moment when equity turns to inequity–within the scope of that one story.

This injustice calls for some resolution. In some stories–like Star Wars, Arrival, Moonlight, and Captain America: Civil War–resolution arrives. In other stories–like Hamlet, Doubt, The Devil Wears Prada, and Manchester by the Sea–the resolution of the initial inequity fails to materialize. The first group tells of triumphs, the second of tragedies.

When determining the character functions of Protagonist and Antagonist, look to the objective context provided by the Overall Story Throughline perspective. What are they trying to achieve? And when it comes to deciding they, assume no superiority of “good” over “bad.”

Good Guys and Bad Guys

Good or bad is a point-of-view, and in the Dramatica theory of story, point-of-view is accounted for in another location within the model. In fact, four points of view exist:

- The Overall Story Throughline and its perspective on their conflict

- The Main Character Throughline and its perspective on my conflict

- The Influence Character Throughline and its perspective on your conflict

- The Relationship Story Throughline and its perspective on our conflict

The Protagonist and Antagonist of a narrative operate within the Overall Story Throughline perspective of They, as in they’re fighting against one another or they’re manipulating one another. Good or bad may play into their pursuits of fighting or manipulating or any other kind of conflict through thematic judgments, but the quality of “good” or “bad” within the context of the Protagonist fails to matter when considering the function of a Protagonist.

The role of a character takes into consideration direction of movement. With the initial inequity created and the Goal to resolve that inequity determined, one character moves towards the achievement of that resolution, the other works to prevent it:

- The Protagonist pursues resolution of the inequity

- The Antagonist avoids or prevents resolution of the inequity

Value judgments of good or bad fail to factor into this determination.

By all accounts sane and righteous, Michael Clayton’s Karen Crowder (Tilda Swinton) is a “bad” guy. Yet, her actions reveal her to be the Protagonist–the one pursuing resolution of the story’s inequity.

The narrative begins when Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson) suffers a manic episode in the middle of a deposition. His actions set off the inequity of the class action lawsuit for everyone in Michael Clayton. As the conglomerate’s chief counsel, Karen pursues a successful resolution of the situation–no matter what it takes.[1]

In How to Train Your Dragon, the destruction of the Viking hometown of Berk upsets the balance of things and drives the Vikings that inhabit that island to seek resolution. Their leader, Stoick (Gerard Butler) pursues a course aimed at training the next generation of dragon killers. His son, Hiccup (Jay Baruchel), does everything in his power to avoid, or prevent, the achievement of this goal. Stoick is the Protagonist of the film, Hiccup the Antagonist. Both play “good” characters in the story.

Manchester by the Sea explores conflict resolution surrounding the death of a single father. Once Joe Chandler (Kyle Chandler) discovers he has ten years left to live, he sets out to find a way for his brother, Lee Chandler (Casey Affleck) to figure into the raising of his son Patrick (Lucas Hedges). While deceased for most of the narrative, Joe functions as Protagonist driving the successful resolution of this inequity. Lee avoids or prevents, the accomplishment of this Goal both consciously and subconsciously. In some respects, Lee’s behavior can be seen as “bad,” yet the Author positions him as a “good” guy throughout the narrative.

When looking dispassionately at the events of a story, a narrative wastes little time considering the goodness or badness of a motivational force in the context of inequity resolution.

A Method for Determining the Protagonist of a Story

This means of determining Protagonist and Antagonist within the context of the Overall Story Goal builds upon the approach discussed in the article on identifying the Goal and Consequence:

- Identify the initial inequity

- Determine what will resolve that inequity

- Set the type of Objective Story Goal that generates that resolution

- The Protagonist pursues that Goal

- The Antagonist prevents or avoids that Goal

Consider the example of Captain America: Civil War. The initial inequity of that narrative begins when the Scarlett Witch (Elizabeth Olsen) uses telekinesis to protect Captain America (Chris Evans) from an explosion. She grabs the explosion and throws it into the air–accidentally killing innocent humanitarian workers in a nearby building. Everything that follows–the Sokovia Accords, helping the Winter Soldier escape the authorities, the fight at the airport, and even the fight between Captain America and Iron Man–claims this act as the initial motivating force.

Stopping the Avengers, or tearing them apart, is the objective Story Goal that resolves that initial inequity. Allowing innocent people to continue to die is the Story Consequence of failing to achieve that Goal.

In a moral world where everyone knows right from wrong and submits to a familiar ethereal authority figure, the idea of tearing the Avengers apart as a Story Goal seems ridiculous. But these are the good guys, why would the story work against them? In this scenario, assumed righteousness determines the objective context, not the events of the story itself.

When determining the integrity of a narrative, the story must reign supreme–not one’s understanding of right or wrong.

Captain America: Civil War goes through great extremes to present a balanced argument on both sides. No one is good, and no one is bad. Fans of the characters may choose their favorite side, but in the end–the narrative claims final word over inequity resolution.

The Bad Guy Protagonist

With the initial inequity determined, and the efforts to resolve that inequity and the consequences that ensue if those efforts fail identified, the Protagonist of Captain America: Civil War comes into focus:

Helmut Zemo. The bad guy.

Zemo (Daniel Brühl) is the character pursuing efforts to tear the Avengers apart. Also, he motivates other characters to consider reasons why the Avengers should be split apart. His effort to generate disinformation in regards to the bomber’s true identity and his endeavor to present a new context for Tony’s familial grief fulfills the objective character element of Consider.

In the Dramatica theory of story, an archetypal Protagonist consists of two motivation elements: Pursuit and Consider. Pursuit is defined as a directed effort to resolve a problem and Consider is described as weighing pros and cons. Put these two motivations into one player under the context of an inequity requiring resolution, and you have a Protagonist.

Opposing Zemo’s efforts to pursue and consider tearing the Avengers apart is the Antagonist of Captain America: Civil War:

Captain America. The good guy.

From the beginning, Captain America reconsiders and inspires others around him to reconsider efforts being made to restrict the Avengers. His struggle to prevent Bucky’s capture and prevent further loss of life amongst the police forces sent to capture Bucky exemplify the character element of Avoid from every angle. His motivation to prevent champions both sides.

Objective character elements consider neither good nor bad; they think force and direction.

In Dramatica, an archetypal Antagonist consists of two motivation elements: Avoid (or Prevent), and Reconsider. Note how these two oppose the Protagonist’s elements of Pursuit and Consider. Avoid is defined as stepping around, preventing or escaping from a problem rather than solving it.

That sounds like Captain America.9

Reconsider is defined as questioning a conclusion based on additional information. Again, Captain America. Put these two elements of Avoid and Reconsider into the same player and you have an Antagonist.

Regardless of whose side they fight on.

The Importance of Remaining Objective

Objective character elements do not see “sides”; they see inequity and the motivation to resolve or prevent resolution, of that inequity. Confusion and misattribution of purpose arrive when the Author projects their understanding of right and wrong upon the motivations of the characters, instead of relying on the actions and decisions of those characters–within the context of the narrative–to determine the morality of the events within a story.

Proper setup of the initial inequity, along with a consistent and cohesive context to consider the motivations of the characters to resolve that inequity, guarantees a reliable and complete narrative.

-

For those who don’t know, Karen participates in some pretty socially unacceptable behavior. ↩

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—a site dedicated to helping writers flourish and finish their very best work. Want to develop your story sense or learn how to fix your current story? Would you enjoy more articles like the one above delivered to your inbox every week? Join the thousands of novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who subscribe to The Narrative First Weekly Newsletter and become a master of your art and craft.

Narrative Structure Gives Purpose to Story

The structure of a narrative defines the purpose of a work. More than simply giving an Audience what they expect, the proper formation of character, plot, theme, and genre communicates the Artist’s deepest Intent. Story structure may not be everything, but everything purposeful needs structure.

Story structure isn’t everything.

Ever since I sat across from Melanie Anne Phillips–one of the co-creators of Dramatica–and she told me that “no one goes to the movies for perfect story structure,” my thoughts stray towards imagining how best to apply that to our work here at Narrative First.

For instance, I recently published the latest in our Storyforming Series–a collection of video tutorials that focus on delivering insights and techniques for rapidly defining the storyform for a particular narrative. The latest episode centers on Woman Woman. In 20 minutes I discuss the observations and choices I made that led to my official analysis of the film.

I’m really excited about this series and can’t wait to add more videos to the series in the coming weeks and months.

Referring back to Melanie’s words, these videos focus on the storyform–something apparently no one goes to the movies to see.

Two decades of experience with Dramatica and narrative says something quite contrary.

Twenty Years That Say Otherwise

Without a doubt, the closer a film or novel or play approaches Dramatica’s concept of a complete story–or storyform–the greater the final result. To Kill a Mockingbird, Hamlet, The Lives of Others, Whiplash, and Inside Out all share the common denominator of complete stories within the eyes of Dramatica.

But they also possess a quality that elevates them above everything else.

Three Different Ways to Preach Story Structure

Recently I found three new films that demand attention: Logan, Get Out, and A Monster Calls.

Logan

Logan was super sad–but thankfully told a complete story. I should say it almost told a complete story. The individual Throughlines were present and well constructed, but the Relationship Story Throughline in particular failed to develop with enough detail. As a result, the film comes off cold and almost heartless.

Sad, but more sad in the logistical sense. Beloved characters die and that’s unfortunate; but the real tragedy of a failed relationship fails to fully materialize.

Logan is an example of story structure told lightly to the point of almost being invisible.

Get Out

Get Out stuns from start to finish. A comedic and dark psychological thriller that, while on the surface appears to not maintain a complete storyform, actually communicates a message so subtle and so sophisticated that many might overlook it. The end result is a film that works its message on you without you even knowing it (just like the film itself!).

Get Out is an example of story structure that creeps up on you without even knowing.

A Monster Calls

A Monster Calls claims the prize of the most heartbreaking and sweetest movies of the last decade. With a concrete story structure that works a kind of Arrival-esque holistic relationship between the Influence Character and Main Character Throughlines, this simple story of a child dealing with loss lightens the burden of those suffering through the same. The end result is a deeply moving message that is apparent, but not preachy.

A Monster Calls is an example of story structure told through imaginative and unique imagery.

Three different ways to relate story structure to an audience: lightly and on the brink of incoherence (Logan), subtle and manipulative (Get Out), and imaginative and unique imagery (A Monster Calls).

Contrast this with the latest from Illumination, Sing!

Story Structure and Nothing Else

Like the films above, Sing! tells a complete story. But quite unlike those examples—that is all the movie does. The structure itself sits right there on the surface, almost to the point where you feel like you can see through to the bones of the narrative. A disturbing and uncomfortable experience, as evidenced by the numerous reviews that qualify the film as “familiar” and “contrived.”

The experience is an obvious one–we all instinctively know how structure works. The Dramatica theory of story explains narrative so accurately because the concepts rest on the notion that a complete story represents a single human mind working to resolve a problem. Thus, we know how story works because we work through problem-solving each and every minute of each and every day.

Unfortunately, seeing it there exposed unsettles the mind. We know how our minds work–but we don’t want it revealed to us. The more we understand why we do the things we do, the less inclined we are to do things we do. Motivation requires blind spots. Remove those blind spots and remove the impetus to problem-solve.

Remove the impetus to watch a movie that does the same.

Giving Them Something More

Story structure insures purpose. The storytelling, the shades and colors the Author–or artist–applies to that structure, elevates the work into something unique and truly lasting. The Authors of the above films do more than simply relate story structure, they tell their stories.

James Mangold (Logan) entertains you with a visceral experience that masks a message of advocating rash and impulsive responses when fighting against those who oppose progress. Jordan Peele (Get Out) hypnotizes you by making you think you’re just watching a scary movie when really he infects you with an approach for getting out of your own head. And Patrick Ness (A Monster Calls) offers a method for dealing with loss and emotional trauma through imagination and storytelling itself.

So yes, Audiences don’t go to the theater to experience perfect story structure–but they do go to see a perfectly structured story.

In this respect our Storyforming videos, and everything else we do at Narrative First, continue to provide that foundation for a great storytelling experience.

The goal is not perfect story structure–but rather, a method for perfectly structuring your story.

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—a site dedicated to helping writers flourish and finish their very best work. Want to develop your story sense or learn how to fix your current story? Would you enjoy more articles like the one above delivered to your inbox every week? Join the thousands of novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who have subscribed to The Narrative First Weekly Newsletter and become a master of your art and craft

Why You Need Four Acts Instead of Three

Many writers break narrative down into Three Acts. After all, what could be simpler than Beginning, Middle, and End? Unfortunately, this idea that the “Middle” somehow stands equivalent to Beginning and End leads many to write incomplete and broken stories.

But isn’t everything a Three-Act structure?

Shooting TIE-Fighters

Everyone knows how the first Star Wars movie ends, right? Moments before Luke Skywalker completes his run, the ghost of Ben Kenobi tells the young farmboy to turn off his targeting computer. Against all better judgment Luke complies, and ends up taking that one perfect shot that destroys everything.

At that very point in time, Luke replaces his motivation to Test his skills with the drive to Trust in something other than himself. This Change of Resolve completes his character arc and saves the day. This act proves the message of the film that by trusting in something outside of yourself you can do impossible things.

Now, here’s the interesting part: that final moment in the trench only works because of the TIE-Fighter Attack Sequence during the escape from the Death Star shortly after Ben’s sacrifice.

Why?

The Context of Acts

One of the purposes of story is to show us the appropriateness and inappropriateness of taking certain actions within different situations or circumstances. The central purpose of an Act is to provide a context for problems the characters face. When a story shifts from one Act to the next, that shift the Audience feels is actually a shift in context.

In Star Wars the four contexts, or Acts, play out like this:

- Act One: Misunderstandings of what happened to the rebel plans and a greater understanding that the Empire means business now (the context of Understanding)

- Act Two - Learning where the plans are and teaching the Rebels that the Death Star can actually destroy an entire planet (the context of Learning)

- Act Three - Fighting against the Empire in a space battle pitting the Milennium Falcon against TIE Fighters and following the Rebels back to their hidden base (the context of Doing)

- Act Four - Moving into position to destroy the Rebel base and taking that one great shot that destroys the Death Star once and for all (the context of Obtaining)

Four contexts, four Acts. Understanding to Learning to Doing to Obtaining. You need to cover all four when writing a story where physical Activities–like laser gun fights, light sword duels, and spaceship battles–depict the kind of conflict within the story.

Different Contexts for One Problem

Each of these Acts provides a context for the central problem of Test in Star Wars. In Act One, the Empire boards a consular’s ship in an attempt to test what they can get away with. In Act Two, the Empire tests the destructive force of the Death Star on Alderaan. In Act Three, Luke and Han test themselves against the Empire…and the Empire provides a semi-challenging test to make it look like they were trying to stop them from escaping (not really). In Act Four, the Rebels test their collective strength against the Empire.

After that fourth context, there is no other place for the story to go. One can’t provide another context for Test within the greater context of problematic Activities. The only thing you could do is start another story, and start the process all over again.

Or you could do what Luke does and stop testing and start trusting.

Complete Stories Require All Contexts

This is why stories require four Acts to function as a complete narrative. Jumping from Learning to Obtaining skips an essential area of exploration. In fact without that Doing context, Luke’s final gesture would appear meaningless.

Some successful stories skip context in order to force the Audience to synthesize their own understanding. 2017 Best Picture Moonlight takes this approach. Jumping from Chiron’s act of violence straight to his new life as Black, the film skips over explaining progress in the Overall Story. What happened in the interim? And more importantly, where did Chiron get the idea of putting up a front?

By leaving these questions up to the Audience to both formulate and answer, Moonlight makes the experience of watching the film deeply personal. Instead of being force-fed a montage of growth and personal re-invention, we supply our own history of development and self-actualization and become a part of the story.

Star Wars is not Moonlight.

An Old Problem Seen in a New Context

If Star Wars skips over the experience of Luke testing himself against the TIE-Fighters from within the Millennium Falcon, no real dilemma–no real choice–exists when it comes to turning off the computer.

In order to successfully provide Luke with the quandary of deciding whether or not to turn off his targeting computer, the narrative needs to grant the boy an opportunity to see testing actually work. The story needs to show Luke a context where Test functions as expected. That way when Ben pipes up and sticks his spiritual nose into the final sequence, Luke has reason to doubt the Old Man and refuse. “Hey, I just showed that I can DO it by myself–I already passed the test, ” he thinks. Why not leave the targeting computer on and see what I can do.

Thankfully for the Rebels, Luke chose otherwise. He tried trusting instead, and that change in approach results in the successful destruction of the Death Star

Explaining the Middle

A narrative requires all four Acts in order to provide an Audience with a comprehensive understanding of the story’s central conflict. By exploring all four contexts, the Author ensures a full and complete evaluation of the story’s problem and potential solution. If the Author mistakingly skips one, the Audience instinctively knows. They sense a hole in the narrative and toss the entire thing out–discounting it as “a bad story.”

Leaving key portions of the “Middle” out works for a film like Moonlight because of its intention to create a deeply personal and subjective experience. For Star Wars–and for a majority of films out there–breaking the Middle down gives greater context.

The Beginning sets the potential; the End reveals the outcome. The Middle functions as transition between the two–a journey that shifts context from one location to the next. To equate the Middle with the previous two is to deny its very essence as a passage of greater meaning and understanding.

Authors use narrative to communicate a message–to argue that a particular approach to solving problems is better than another. The passing through is very bit as important as the final result. By fully depicting the implications of deciding to go one way or the other, Authors ensure their message–or argument–rings true and remains in the hearts and minds of their Audiences.

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—fine suppliers of expert story advice. Want to develop your story sense? Join the other novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who have enrolled in the Dramatica® Mentorship Program and become a master of your art and craft.

Losing Sight of Your Main Character

Audiences come to story with the hope of experiencing the new. Key to drawing them in and keeping them there lies with the proper application of the Main Character’s perspective. Lose sight of the Main Character and writers risk losing their Audience.

A disturbing trend of late seems to be on the rise within narrative fiction: that of the undefined or ill-defined Main Character Throughline. The Croods, End of Watch, Prometheus, and the latest James Bond thriller Skyfall all fail to offer Audiences consistent points-of-view from their Main Characters. Sure, they might entertain us with visual delights from worlds light-years away or they might engage us viscerally with uniformed life on the streets of L.A., but without consistency in where we witness these events from the experience falls into insignificance.

As popular as Skyfall was, what exactly was the film trying to say? Failure to recall key moments or arcs of character often indicates a failed and broken story. Try it with this latest Bond film and consternation surely ensues. The film began as an exploration of what it means to be at the end of one’s career–a new young hipster Q, the physical struggle to keep up with the demands of the job (holding on to the elevator platform)–but then somehow lost track. The story clearly sets up the issues of Bond aging out, yet for some reason forgot to address these problems shortly after the first act turn. Like an amusement park ride, Skyfall offers thrills, chills and spills, that last for a moment yet ring hollow days after.

Story can be so much more.

A Way In

The Main Character offers more than simply someone to cheer for. This unique and central character grants the Audience a way into the mind of a story. Dramatica theory (Narrative Science) suggests that the Main Character holds the first-person “I” perspective on the problems within a story. From this point-of-view the Audience gets to experience what it is like to personally face this issue.

Contrast this with another important perspective, the “You” point-of-view offered by the Influence Character. The Audience does not experience what it is like to actually be this character, but rather watches what this character does and how they behave. This experience of watching another work through a problem “influences” us the Main Character (as the Audience we have assumed the collective position of the Main Character) to reconsider our own issues and how we approach them.

Thus, the Main Character Throughline offers the Audience a reference point from which to interpret everything that happens on-screen or in print. When arguing a particular approach to problem-solving it becomes necessary to establish who we’re looking at and who is looking at us. Conflict does not occur within one viewpoint but rather between disparate viewpoints. You and I. Because of this reality, perspective regions supreme.

The Dangers of Altering Perspectives

Baz Luhrman’s take on The Great Gatsby should prove to be interesting. Will he repeat the all-too-common mistake of interpreting Nick Carraway’s narration as simply that: narration? Most adaptations fail to see the thematic connection between Nick’s point-of-view and the rest of the story.

From the looks of the film’s the trailer (set to release in May 2013), it appears as if the great Gats himself (Leonardo DiCaprio) will assume the Main Character’s point-of-view while Daisy Buchanan (Carey Mulligan) will take on the Influence Character role. This runs counter to what can be found in the original novel. According to the official Dramatica analysis of The Great Gatsby, it is Nick (Tobey Maguire in the film) that operates as the Main Character while Gatsby actually takes on the Influence Character role. True, we get hints of a first-person perspective from Nick (Tobey Maguire) within the trailer, but the majority of scenes depict the struggles of Gatsby and his relationship with Daisy.

Altering these key points-of-view threatens the meaning of the story. Classic novels claim their immortal status for a reason. Are we looking at Gatsby and his over-the-top actions, or are we experiencing what it is like to be someone who acts that way? The answer to that question will define what the Audience appreciates from the story’s events. Altering the perspectives because of a fascination with a particular performance (which seems to be the case here) can lead to confusion over the message of a story.

Lessons from the Past

Consider Neil Simon’s classic Barefoot in the Park and the Main Character of that story: Paul Bratter (Robert Redford). Clearly the original play called for us to see Corie (Jane Fonda) through Paul’s eyes: Simon went so far as to even call Paul out for being a “watcher, not a Do-er.” Yet here too, the adaptation devoted so much of its attention on Fonda’s inspired and captivating performance that it lost sight of Paul’s personal issues. Many probably don’t even remember what Paul’s issues were (assuming they’ve even seen the film).

The Dramatica analysis of Barefoot in the Park correctly identifies Paul’s issues of being overly-responsible when it comes to juggling time spent with his new wife and time spent with his new job. His fuddy-duddy “stuffed-shirt” nature runs counter to Corie’s vivacious and randy ways and drives a huge wedge into their six-day old marriage. Coming to terms with this dysfunctional way of thinking and appreciating the value of freely running barefoot in the park resolves the problems within the story.

Unfortunately the concentration on Fonda’s performance undermines this message–something clearly important to the original Author (why else would he title it “Barefoot in the Park”?). Like Bond in Skyfall, Paul’s struggle falls to the wayside threatening the Author’s original intent in the process.

Adaptation and Medium

Part of the problem lies in the fact that this film originally existed as a play. It becomes rather difficult to establish perspective when the Audience’s actual point-of-view towards the performance of a play remains fixed (i.e. in their seats, watching the stage). Short of extended soliloquies the stage offers little help for writers attempting to center their Audience. In film, shot selection and composition can set and delineate perspective concretely. In The Shawshank Redemption the Audience experiences what it is like to walk the long hall down to a parole-board meeting and what it is like to become friends with a cold-blooded killer like Andy Dufresne by witnessing these events through Red’s eyes. Like Nick’s narration in The Great Gatsby, Red’s narration offers a glimpse into what it is like to think like an institutionalized man–supporting the system instead of standing up against it.

The same technique could have been applied to the film adaptation of Barefoot in the Park with great effect. Occasionally the writer affords the Audience this viewpoint–the Staten Island ferry scene wherein Paul confesses Corie’s apparent sins to his mother-in-law (“Just look at her”)–but scenes like this come few and far-between.

Thankfully–and quite unlike Skyfall–Paul’s throughline comes full circle. The resolution of his throughline mixes with that of the larger story granting the Audience a satisfying and emotionally fulfilling ending.

The Present of a New Perspective

Writers must keep the point-of-views solid throughout their stories lest they wish to severely disorient those engaging with their work. Centering the Audience with the conflicting perspectives of both Main Character and Influence Character helps clarify what the Author wishes to say with their work. Audiences want meaning, they want something more from their stories. Authors have the ability to provide them with this unique gift–they only need to better understand how to package it.

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—fine suppliers of expert story advice. Want to become a master writer with Dramatica? Join the other novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who have enrolled in our Dramatica® Mentorship Program and accelerate the development of your own sense of story.

Genius Doesn’t Know Genius

For almost two decades, the artists at Pixar Animation Studios have delighted audiences everywhere with captivating and compelling stories. Creatives everywhere have long respected the studio’s ability to fuse heart and soul into enduring classics of narrative. How is it then that Pixar apparently has no idea how they do what they do?

Last summer, Pixar story artist Emma Coats tweeted a list of 22 story “rules” she learned while working there. Retweeted and passed around ad-nauseam, many took to the list in the hopes of discovering the secrets to the studio’s long time success. Unfortunately, what they found were mostly superficial tips to help writers during the process of writing–not necessarily the reason why Pixar’s film excel over all others.

To be fair, these rules were originally presented as “tweets” and thus were constricted by the 140 character limit. Nothing much of value can be presented in such a short space. Still, many continue to uphold this list as great insight into the construction of a Pixar-like story.

The real secret, it turns out, can be found elsewhere.

The Not-So Helpful

First up, the bad:

Rule 3: Trying for theme is important, but you won’t see what the story is actually about til you’re at the end of it. Now rewrite.

Another call to simply trust the process–woefully turning a blind eye to meaningless writing in the hopes that it will all somehow “magically” work out. Creative writing certainly requires a fair amount of exploration, but the sooner you know what it is you want to say the sooner you can actually go about writing what it is you want to say. The danger, of course, lies in beginning production before that theme–or purpose–has made itself known. Cramming it in last minute requires multiple re-dos and countless hours of overtime.

Rule 4: Once upon a time there was ____. Every day, ____. One day ____. Because of that, ____. Because of that, ____. Until finally ____.

A formula for writing a tale? No thanks. If one wanted to put out a statement (which is all a tale really is) then one could use Twitter or a Facebook update. Stories argue, tales state. Unfortunately the tip above usually leads to the latter.

The balance of the less-than-helpful tips lie somewhere between simple writing advice and the kind of feel-good hand-holding typical of a weekend writer’s retreat in Sedona. “You have to know yourself”, “You gotta identify with your situation/characters”, and “Let go even if it’s not perfect” do not really reveal the reason why so many of Pixar films remain beloved in the hearts of millions let alone how to construct one of your own. *When you’re stuck, make a list of what WOULDN’T happen next“* and Discount the 1st thing that comes to mind work as great brainstorming techniques but they don’t expose any meaningful secret approach. If it is really true that ”those who can’t do, teach“ then the corollary to that must be ”those who can, can’t teach."

Extracting the Gems

That said, some of these rules provide useful concrete information that many can actually use to structure a meaningful story worthy of the Pixar name. Some of these actually explain why their films work so well. The first that stands out:

Rule 16: What are the stakes? Give us reason to root for the character. What happens if they don’t succeed? Stack the odds against.

Dramatica (Narrative Science theory) refers to these stakes as the Story Consequences. Most writers understand the concept of Goals and how they motivate characters to take action, but relatively few understand the importance of providing their characters consequences should they fail. Both exist in a story and both require each other for meaning. In Toy Story, failure to keep up with the move condemns the toys to a life of perpetual panic. Consequences work as a motivator to help propel a story forward–a solid tip that gives a foundation for good strong narrative.

Rule 6: What is your character good at, comfortable with? Throw the polar opposite at them. Challenge them. How do they deal?

Very helpful. If one wishes to write a story about the first African-American baseball player and all the issues of preconception that run along with such a predicament, throwing his “polar opposite” against him would help increase the conflict and give him reason to grow. But what would that opposite be? Someone who doesn’t believe he should be playing ball because of the color of his skin? That would challenge him, but it wouldn’t really challenge his own personal point-of-view as he would have been dealing with that his entire life already. Better to throw someone in there who shares a similar predicament but goes about solving it in a different and “opposite” way.

Thankfully the current model of Dramatica provides us with clues where to find this similar, yet different character through its concept of Dynamic Pairs. Pursuit and Avoid, Faith and Disbelief, Perception and Actuality all work as dynamic opposites to each other–put the two Dynamic Pairs in the same room and watch the sparks fly.

In the case of our famed baseball player we would want to construct an Influence Character that was deep in denial. Perhaps an aged coach well beyond his years, obsessed with bringing a losing team to the World Series. Or maybe the baseball player’s wife who, regardless of all the talk of extra-martial affairs and excessive drinking on the part of her husband, stands by his side through thick and thin. Either way, this dynamically “opposite” character would force the baseball player to examine his own issues of prejudice and preconception and whether or not he was living in denial.

So yes, challenging characters to deal with their issues by providing “polar opposites” certainly helps in the construction of a story. Again, concrete, solid advice that can help one write a powerful story of their own.

Rule 7: Come up with your ending before you figure out your middle. Seriously. Endings are hard, get yours working up front.

Another good one, even if it seemingly runs counter to tip #3 above. Should writers go with the flow or are they supposed to know where they’re going? A meaningful ending bases itself on the thematic arguments that preceded them. They work together to help define the Author’s argument. Which brings us to…

Rule 14: Why must you tell THIS story? What’s the belief burning within you that your story feeds off of? That’s the heart of it.

The argument an Author makes runs tantamount to all. The “belief burning within you” lies in the Author’s point-of-view on how to solve a particular problem. Narrative Science helps to give those beliefs a reference point and offers suggestions for formatting a strong and coherent argument to support that belief.

Genius Defined

While fun to retweet and pass along, the majority of these 22 rules of Pixar storytelling do little to explain the rampant success of that studio during their first decade. If it is true that these were gleaned from “senior colleagues” then it is quite possible that those responsible for such great storytelling have no idea how they were really able to get there in the first place.

The real secret to Pixar’s undeniable success lies in their ability to write complete stories. Whether it be the dynamic clash between Woody and Buzz in the first Toy Story or the thematic interplay between Linguini and Remy in Ratatouille, each and every story effectively argued a specific approach to solving a problem. Managing to incorporate all four throughlines necessary to convey this message over a decade of production astounds those who managed to only do so maybe once every ten years. Pick any film and one can easily identify the Overall Story Throughline, the Main Character Throughline, the Influence Character Throughline and the Relationship Story Throughline. Other studios and other films can usually only claim to be able to do the first two (though some even struggle with that). Finding Nemo went so far as to weave a second smaller, yet no less important, sub-story into the final product. A truly remarkable accomplishment that bears full witness.

The reason for the apparent drop-off in love for their most recent films? A departure from these principles of solid story structure. Both Brave and Cars 2 fail to weave convincing arguments, the former going so far as to have both principal characters flip their point-of-views–a tragedy leaving many wondering what the film was even trying to say (beyond how cool Merida’s hair looked).

For the genius to continue and for those interested in repeating that success, an understanding of how narrative works to argue an approach to problem-solving becomes necessary. Narrative Science theory, and Dramatica in particular, provides that insight. It provides the secret “keys” everyone hoped to find when they first stumble across these 22 rules of storytelling. Understanding why so many of their films appeal to both the hearts and minds of countless millions can go a long way towards insuring the same kind of love and acceptance in one’s own work.

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—fine suppliers of expert story advice. Want to become a master writer with Dramatica? Join the other novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who have enrolled in our Dramatica® Mentorship Program and accelerate the development of your own sense of story.

Dramatica Simplified

Dramatica can seem a bit overwhelming when you first start out. One need only flip casually through the theory book dictionary before instantly coming to the conclusion, “This is insane!”

But greater comprehension comes with time. Eventually terms like Universe, Preconscious, and even Conceptualizing as a Story Concern begin to make sense in a way that can significantly benefit the process of writing. The difficulties with the language slowly fade as one realizes the reason for their foreign nature.

They’re Complicated Because They’re Accurate

If the terms were simpler, or put into more “writer-friendlier” terms, they might be easier to comprehend, but they would distill down the power of Dramatica. The theory seeks to accurately map out the psychological processes of the human mind. The mind is not a simple machine. And why should it be? It provides us with a mechanism for determining meaning, a way to buttress context against context.

If the theory was painted in broader strokes, the Main Character would always be the Protagonist, want and need would replace Problem and Solution, and metamorphosis/transformation would replace Resolve and Growth. In other words, it would be just like every other story theory.

However, if you don’t mind dialing the accuracy back a little, the initial Eight Questions the theory poses become easier to deal with.

A Simpler Take on Story Structure

- There are two major characters in your story. One who will significantly change his world view and one who will stand his ground.

- One of these characters will like to build things, use their hands, and get things done. The other would rather change themselves or act a different way.

- One will want to find how things fit together, while the other would prefer to solve problems.

- In your story you will have good guys and bad guys. In some stories the good guys win. In other stories the good guys lose and the bad guys win.

- The people you are rooting for will feel like they are running out of time or running out of options. Again, it doesn’t matter, just keep it consistent and don’t change it halfway through.

- Your story will either have major events that happen to these characters or they themselves will decide to take action. Both will be in there, but one will feel stronger than the other.

- The character you care about the most will either be at peace at the end of your story or he/she will still feel at odds with the world around them.

- This same character will grow throughout the story by trying something new or by discarding an old trait.

The above relate (in order) to: Main Character Resolve, Main Character Approach, Main Character Mental Sex, Story Outcome, Story Limit, Story Driver, Story Judgment, and Main Character Growth. When you first set out to map your story, the above eight questions may be a convenient and easy way to start.

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—fine suppliers of expert story advice. Want to become a master writer with Dramatica? Join the other novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who have taken our a Dramatica® Mentorship Program and accelerate the development of your own sense of story.

Finding the Major Dramatic Question of Your Story

Writers love to place themselves in the shoes of their characters. Pretending to be someone else and emoting with the needs and desires of another mark the starting block of the writer’s initial foray into a lifetime of discovery. One problem: without a proper map they end up lost and confused, doubling back on themselves without even noticing.

The first artice in this series on Plotting Your Story with Dramatica recognized The Difference Between Becoming and Being in Dramatica. Understanding the various Types of conflict that exist in a story and how they feel shifting from one to another built the foundation for Identifying the Number of Acts in Your Story, the second article in the series. With that knowledge in hand, we now steer our foucs towards answering the question of dramatic tension within a story.

An Objectified View of Story

Dramatica deals almost entirely with the objective view of a story. While The Audience Appreciations of Story like Reach, Essence, Tendency, and Nature bridge the gap between the objective and subjective, this objectified view of narrative is what separates Dramatica from everyone else. It is why some refer to its approach as too “abstract” and why others find the terminology “obtuse” and over-complicated. Writers write from inside the point-of-view of their characters; anything outside appears foreign and manufactured.

The unfortunate side-effect of remaining locked in a subjective view rests in the very definition of a subjectified view: blind spots. Without access to the totality of everything going on around us, we often mistake our perceptions for reality. Films like The Sixth Sense, The Usual Suspects, and American Beauty explore this exact problem.

However, a completely objective view lacks the one thing that subjectivity claims as its own: compassion. The phrase One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter describes the ability of the subjective view to empathize and care about the particular point-of-view one takes. In story, we want the Audience to relate to our characters and to be moved by their thoughts, their words, and their actions.

A powerful and meaningful narrative finds substance in both the subjective and objective views. The greatest writers dive into their stories and write subjectively, and then come up for air and take a more measured and objective view of their words. After assessing and determining the moments of subjective indulgence, they dive back down and make the necessary adjustments.

Dramatica helps with the objective part of the process. Countless other paradigms and understandings of story help with the subjective part—only, they don’t make attempts to bridge the gap between the two. Our new understanding of Dramatica makes it possible to do both.

A Question of Dramatic Tension

Google “the question of dramatic tension” and you’ll find many articles detailing the subjective approach to writing a story. They focus on methods for keeping the audience “hooked” into the story, and for keeping up audience involvement. The blog Writing for Theatre: Tips & Tricks for Beginner Playwrights has this to say about dramatic tension:

One of the main ways of creating tension is by planting questions in the “mind” of the audience. As soon as a play begins, audiences have questions they want answered by the playwright. Where and when is the play set and why? What are the characters doing? Are they important characters? Where will the play head? What is the theme of the story?

Many refer to the question on everyone’s mind in the Audience as the Major Dramatic Question, or “Central” Dramatic Question. As Doug Eboch, the writer behind Sweet Home Alabama explains in his post on The Dramatic Question:

The Dramatic Question is the structural spine of your story. Remember how I said last time that a story consists of a character, a dilemma and a resolution? On some level all Dramatic Questions can be boiled down to “Will the character solve their dilemma?” Of course that’s not very helpful to the writer trying to crack a story. You need to ask that question with the specifics of your character and dilemma.

The above bears repeating:

“Of course that’s not very helpful to the writer trying to crack a story.”

This is where the subjective approach to constructing a story breaks down. Even if you ask the question with “the specifics of your character and dilemma” you will find yourself no further along than before you asked…because you will still be trying to construct the foundation for a narrative that affects each and every character from a subjective point-of-view. Subjectively, we are all blind to what is really going on. Why should it be any different from the point-of-view of a character?

Subjective Blind Spots

On Scott W. Smith’s blog Screenwriting from Iowa he presents a collection of Major Dramatic Question examples from around the globe:

- E.T.: Will E.T. get home?

- The Silence of the Lambs: Will Clarice catch Buffalo Bill?

- Erin Brockovich: Will Erin bring justice to a small town?

- Finding Nemo: Will Marlin find his son?

Anyone familiar with Dramatica will notice that each of these questions finds genesis within the Story Goal of the narrative:

A Goal is that which the Protagonist of a story hopes to achieve. As such, it need not be an object. The Goal might be a state of mind or enlightenment; a feeling or attitude, a degree or kind of knowledge, desire or ability.

And interpreting the essence of these questions objectively, one could easily assign Obtaining as the Story Goal for each of these stories:

Obtaining includes not only that which is possessed but also that which is achieved. For example, one might obtain a law degree or the love of a parent. One can also obtain a condition, such as obtaining a smoothly operating political system. Whether it refers to a mental or physical state or process, obtaining describes the concept of attaining.

E.T. achieves freedom. Clarice captures Buffalo Bill. Erin brings justice. And Marlin finds Nemo.

Unfortunately, if you were to set Dramatica’s story engine to Obtaining for all of those films you would be short one Oscar for screenwriting.

Subjectivity Breeds Blindness

E.T. the Extra Terrestrial, Erin Brockovich, and Finding Nemo find conflict in their individual stories through Obtaining. The government agents try to capture the alien and the kids try to win his freedom in E.T.; Erin digs into the case and tracks down evidence of coruption in Erin Brockovich; Marlin, Dory, and Nemo escape from sharks, whales, and aqauriums in Finding Nemo. If the question of Dramatic Tension sets the spine of a story then yes, questions of Obtaining fit…for these films.

The Silence of the Lambs is an entirely different monster altogether. Rather than focusing on achieving or Obtaining, this film gathers its attention on How Things are Changing:

The FBI is concerned with its discovery of an increasing number of victims and the progress it is making toward locating Buffalo Bill; Clarice Starling is concerned with her progress as an FBI trainee; Buffalo Bill is concerned with the progress of his “suit of skin”; Hannibal Lecter is concerned with the progress being made toward better accommodations (and escape); etc.

Writing Silence from the point-of-view of Will Clarice catch Buffalo Bill? results in all these missed opportunities for potential conflict. Where would Hannibal Lecter be or Buffalo Bill if it was simply about capturing the villain? Digging into the case and tracking down clues—like you would in an Obtaining story like Erin Brockovich—leaves out Clarice’s progress as a trainee, Lecter’s progress towards better accomodations, and more importantly—the progression of victims at the mercy of Bill’s developing “suit of skin.”

Asking from a Place of Objectivity

Once we identify the source of conflict in The Silence of the Lambs as progress, or How Things are Changing, it becomes easier to identify the true dramatic question of the film:

Will Clarice be able to stem the tide of Buffalo Bill’s murderous rampage?

Far more interesting, and far more compelling than simply whether or not she will capture the bad guy, asking a question that brings to mind all the devolving forces working against Clarice inspires greater creativity and sophistication within the narrative. The artistry that sets Silence apart from all other films in this Genre is this focus on the rising tide as the center of conflict—not capturing and evading. Focusing on the “wants and needs” and “dilemma” of the central character would only guarantee mediocrity.

And the Academy doesn’t hand out awards for mediocrity.

An Approach that Answers Everything

The problem with asking dramatic questions and taking a subjective approach to structuring a story lies in the very nature of subjectivity—you don’t see everything that is going on. In fact, this approach seems ludicrous when you consider that an Author is the God of their story—they know and see everything!

Anchoring the subjective point-of-view to an objective understanding of the true nature of conflict within a narrative is the only way to guarantee a powerful and meaningful story.

By all means, write from within. Take that character’s point-of-view and run with it. But anchor it to an objective view that ties plot, theme, character, and genre into one.

Ask questions, but know that those questions have answers. Dramatica’s concept of the Story Goal helps writers nail down and ask the right question by asking them to identify the true nature of their story’s conflict. In fact, Dramatica goes one step further by helping to provide the answer to that question through its concept of the Story Outcome.

Subjectively we can only ask as we experience a story. That is why approaches to writing from within focus on these questions of dramatic tension. Why restrict ourselves as writers to simply asking questions, when there exists a foundation for both the question and the answer?

This article originally appeared on Narrative First—fine suppliers of expert story advice. Want to become a master writer with Dramatica? Join the other novelists, screenwriters, and playwrights who have taken our a Dramatica® Mentorship Program and accelerate the development of your own sense of story.

Identifying the Number of Acts in Your Story

In Hollywood, every film is a Three Act structure. Roam the halls of the story department at one of the big animation studios or saunter in to a lunch meeting for production executives on a live-action film and you encounter the same sight on every white board: a sequence of events broken down into three separate sections.

But not every story is a Three Act structure.

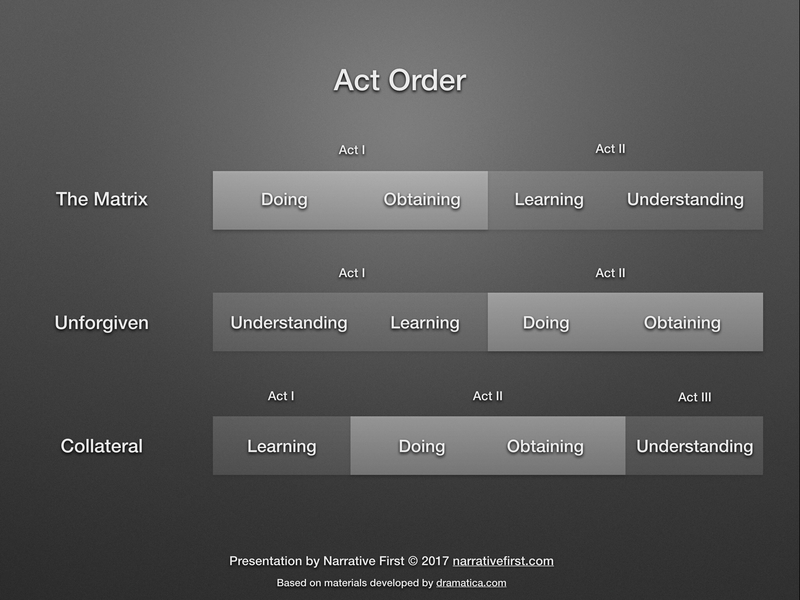

Some narratives tell the story of a rise to power followed by a great fall (The Dark Knight); others start with the fall, then end with the rise (The Matrix). These stories split dramatic tension into Two Acts. Any attempt to force them into a Three Act structure only encourages dissension and disagreement among collaborators.

Still others–like The Godfather or Platoon–break off into four distinct movements. Almost episodic in nature, yet still tied together thematically at the core, these stories clearly function on top of a Four Act structure. Force a Three Act paradigm here and you risk breaking a masterpiece.

The key to effortless development dwells in understanding the type of narrative structure your particular story requires. Every complete story feels complete because it addresses the different contexts where problems find solutions. Each Throughline focuses on one particular area of conflict, and each of these areas divides naturally into four different Types of Conflict.

Types of Conflict

Problems of Activities split off into Understanding problems, Doing problems, Gathering Information problems, and Obtaining problems. Chris Huntley, one of the co-creators of the Dramatica theory of story, describes the difference between these four Types in the Dramatica Users Group narrative analysis of Zootopia at the 1:21:40 mark in this video:

As Chris explains, Doing is about engaging or not engaging in an activity whereas Obtaining is about achievement or loss. Both require “doing” but the focus in each instance is different. Understanding is figuring out how things are related to one another whereas Gathering Information is the process of learning about something.

Observe the athlete:

- Some love the training and the preparing, the quintessential perpetual student (Gathering Information)

- Some want to win a gold medal (Obtaining)

- Some want to simply do the exercise all the time (Doing)

- Some want to understand the effects of training on their body and life (Understanding)

Again, focus is key. Some enjoy reading, while others want to read all of the books in a series and perhaps own the largest library in the world. The former focus on the Doing, the latter on Obtaining. Think of these different Types of Conflict as different dimensions of the area of conflict they explore; in this case, Doing, Obtaining, Learning, and Understanding reflect different dimensions of an activity.